In 2004, San Antonio dentist Robbie Henwood and his physician wife went to estate-planning and personal-injury lawyer Christopher “Chris” Pettit to get their wills in order before taking a trip.

He convinced the Henwoods to set up a trust and later to invest their modest retirement savings with him. After a suicidal gunman killed their son, 36-year-old San Diego police officer Jeremy Henwood, in 2011, the couple gave Pettit the death benefits and life insurance proceeds to invest, as well.

“He told us the money you invest will be safe,” Henwood said, recalling Pettit’s assurances. “And not to worry, the funds were all insured. If the stock market went sideways, you still get your principal back and interest.”

Over the years, Pettit earned the trust of the Henwoods and dozens of other clients, becoming a “friend” and “family confidant.”

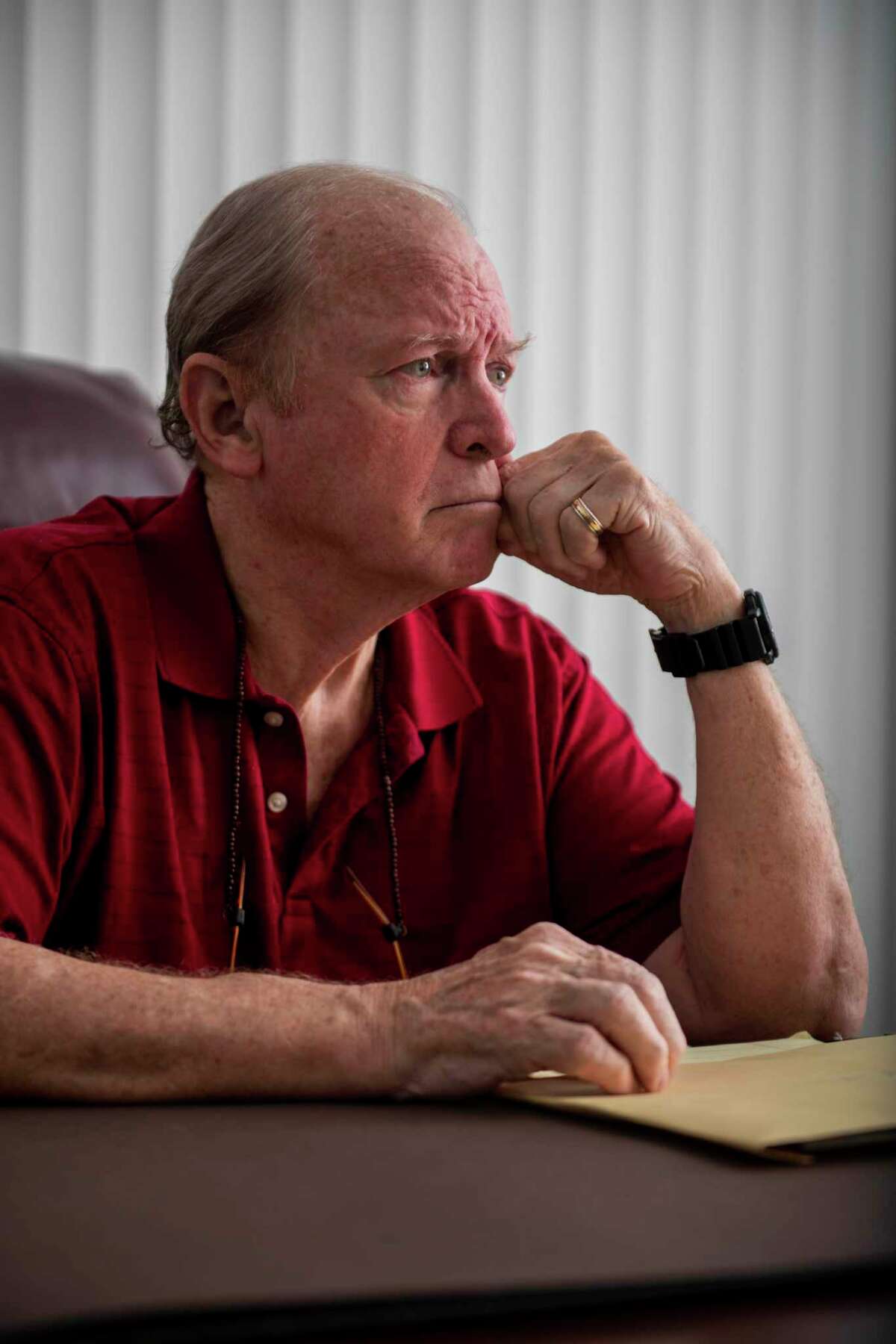

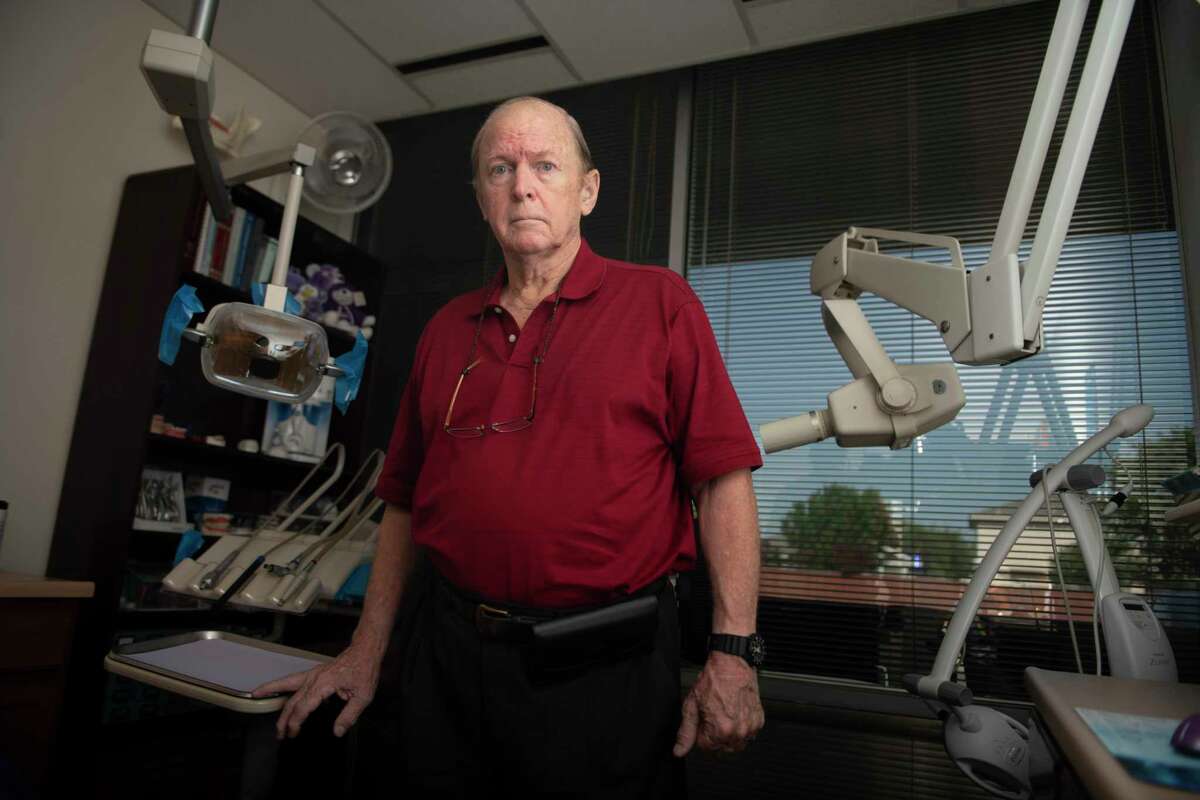

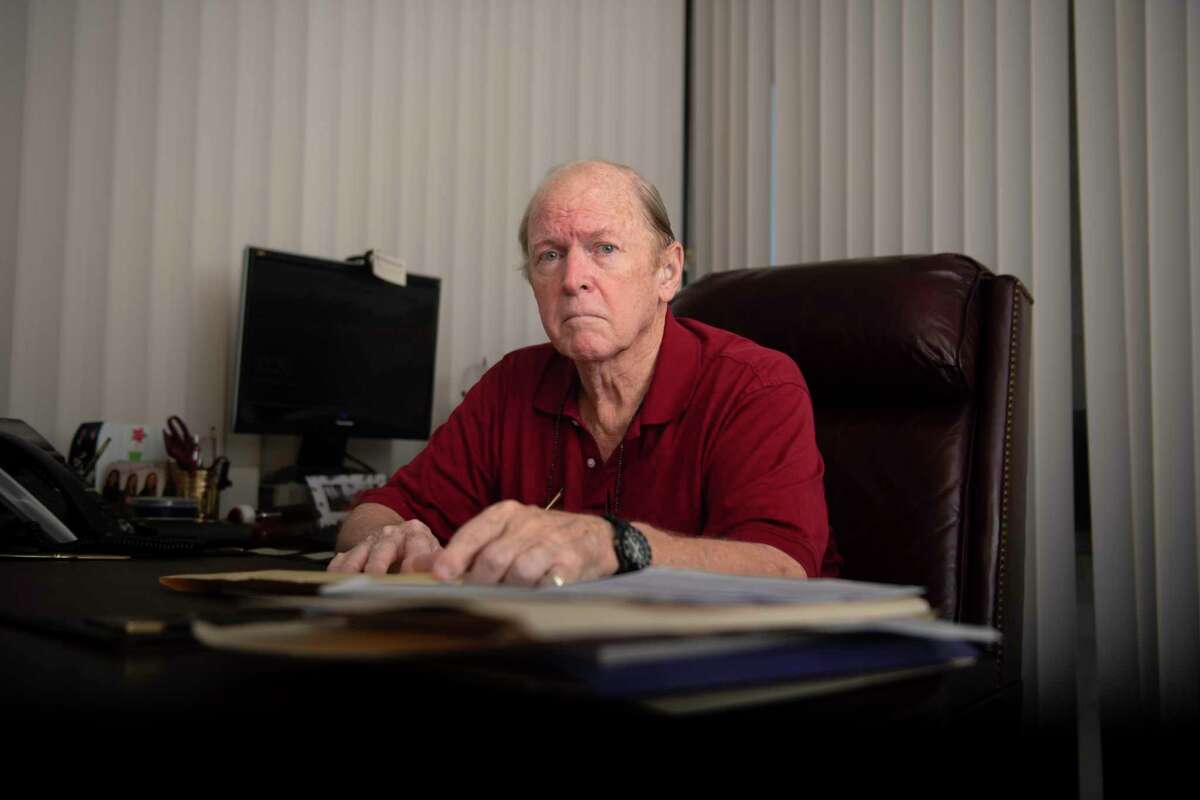

“I’ll tell you, this guy’s friendship and his charm overwhelmed me,” said Henwood, 74, now retired. He said he had more than $1.2 million invested with Pettit.

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

It all changed this year. He suddenly became hard to reach, not returning clients’ calls or responding to their emails. Pettit’s staff explained his absences by telling Henwood the attorney had a heart condition and was under medical care.

But Pettit couldn’t brush off some clients so easily. When a flurry of lawsuits were filed this spring by clients alleging they’d been fleeced, the walls began closing in on him. In a couple of those cases, Pettit seemingly waved a white flag by agreeing to judgments.

In one, Pettit admitted he “misappropriated and dissipated” a trust and was ordered to pay more than $10 million in damages. In another, the court found he had “knowingly and intentionally committed theft of $908,148.47.”

In a span of less than 10 days beginning May 24, Pettit gave up his law license — to avoid discipline — and sought bankruptcy protection for himself and his now-shuttered law firm.

His personal bankruptcy is among the largest ever filed in San Antonio. In his Chapter 11 petition, Pettit listed assets of $27.8 million and debts of $115.2 million. His firm, Chris Pettit & Associates, reported assets valued at no more than $50,000.

One creditor’s lawyer told a bankruptcy judge that $50 million or more has gone missing from clients’ accounts.

The FBI has been investigating and, according to a source, so has the Internal Revenue Service.

A lawyer who has been representing Pettit in the civil litigation didn’t respond to a request for comment. Any pending suits are on hold because of the bankruptcies.

On Friday, a judge approved the appointment of San Antonio attorney Eric Terry as bankruptcy trustee. Terry’s duties will include hiring law firms and forensic accountants to track down where the money went.

Retired dentist Robbie Henwood invested his life savings with Christopher “Chris” Pettit, the now ex-San Antonio attorney accused of fleecing clients.

Carlos Javier Sanchez, ContributorMeanwhile, Henwood and other clients — many in their twilight years — are left trying to figure out how they’re going to survive without the life savings they had been counting on for retirement.

“I’m pretty much too old to get a job,” Henwood said. “I don’t have enough money to pay household expenses past maybe a year. And then I don’t have any way of replacing it or regaining any of it.”

Henwood, coping with the death of his wife of 51 years earlier this year, has heard rumblings that clients may receive just pennies on the dollar. He guessed that might give him another year to cover his living expenses, but he doesn’t know what to expect after that.

“Start selling my house, my clothes, my car?” he said. “Move on to the street? That’s what he’s done to more than just me.”

‘Different kind of guy’

Nothing in Pettit’s background gave much hint of the troubles ahead but there were red flags that many failed to notice.

On one of his law firm’s two websites, which have been taken down since he ceased practicing law, Pettit said he graduated with “distinction” from the University of Dallas, a Catholic university where he studied economics. He obtained his law degree from St. Mary’s University School of Law in 1991.

Pettit, 55, described himself as an “accomplished and dynamic speaker” who put on educational seminars on the “importance of proper estate planning and other insurance issues.”

He also claimed he taught law at the National Christian School of Law and Our Lady of the Lake University. But the National Christian School of Law doesn’t appear to exist and an OLLU spokesman said its records indicate Pettit never taught there.

San Antonio attorney David Balmer, who worked in Pettit’s law firm from about 2000 to early 2006, remembered Pettit’s “propensity to embellish things.”

“He was just a different kind of guy,” Balmer said.

No one else at the law firm touched the checkbook, Balmer said, even as the practice grew in size and added staff. Pettit’s listing on the State Bar of Texas’ website shows the firm had from six to 10 lawyers.

“He was the only one who did any of the banking, at least when I was there,” Balmer added. “And I heard through the grapevine that it was still that way. I imagine there are quite a few people who were over there recently who are happy about that now because they can say, ‘Hey, I never touched that checkbook.’”

Former Bexar County Probate Judge Kelly Cross joined Pettit’s law office for about 10 months before quitting in March. She declined to say what led to her abrupt departure — other than it made her “uncomfortable.”

“I will say that I am so distressed and hurt, what he did to people,” Cross said. “I took my suspicions immediately to where they needed to go. Immediately. And quit immediately.”

Former Bexar County Probate Judge Kelly Cross worked in Christopher “Chris” Pettit’s law firm for about 10 months until she said she quit in March after seeing something that that made her “uncomfortable.” She said she took her “suspicions immediately to where they needed to go.

Balmer recalled that when he left Pettit’s firm in 2006, it was doing a lot of trust work and estate planning involving trusts.

“The allegations that I see now, where he’s naming himself trustee and financial planner for all these people, there was none of that,” he said. “We were just strictly lawyers doing estate plans.”

Balmer and Pettit co-authored a book on estate and financial planning titled “Total Wealth Management” in the early 2000s. Amazon lists the American Academy of Estate Planning Attorneys as the publisher.

Pettit had been a member of the academy, which helps lawyers build their legal practices, but he failed to meet its continuing legal education requirements in 2020.

Balmer recalled how the academy told lawyers about getting “cross-licensed” to provide financial planning services and become a “one-stop shop” for their law clients. Previously, he said, lawyers in Pettit’s firm would simply refer clients to other financial planners.

“There was none of that in-house stuff,” said Balmer, who is not a financial planner. “I think that’s where the troubles come in with Chris and any lawyers that might be in that area, when they start thinking, ‘I’ll just do everything for them. I’ll be their financial guy.’”

In 2012, Pettit ran afoul of the State Bar of Texas. It publicly reprimanded him after finding he “failed to ensure that his non-lawyer associate’s conduct was compatible with the professional obligations of a lawyer.” It provided no other details, but fined him $850.

Investment adviser

Three years later, Pettit earned a Series 65 securities license qualifying him to provide investing and general financial advice.

He became affiliated with the Austin office of Triad Advisors, a brokerage and investment firm based in Georgia. Triad became part of Advisor Group, which bills itself as the largest network of independent wealth management firms, in a 2020 deal.

At some point, based on letters submitted as exhibits in cases against him, Pettit would either “recommend” or “propose” to some of his law clients that they invest in what appear to be municipal bonds.

It couldn’t be determined if Pettit recommended investments to clients and then referred them to Triad to make the investments. Some suspect that in at least some of the cases, he never made the investments.

Henwood, the retired dentist, recalled Pettit said his money would be invested in the “secondary bond market,” though he didn’t know any details.

Some of the investments Pettit suggested don’t seem to exist, though.

In multiple letters to a San Antonio couple on his law firm’s letterhead, he made the same investment recommendations in 2019 and 2020.

Among them was one with the “Hudson County NJ MPT Authority.” James Kennelly, a spokesman for Hudson County, New Jersey, never heard of it.

“The only ‘Authority’ Hudson County operates is the Hudson County Improvement Authority (HCIA), which has never been referenced in any way as the ‘MPT,’” he said in an email. “We do not operate any agency with the initials MPT.”

Another investment Pettit recommended was the “VA Housing Settlement Auth.” A search on the website of Electronic Municipal Market Access, a repository of information on municipal securities, failed to turn up anything with that name. A spokeswoman for Virginia Housing, a state agency that helps residents obtain affordable housing, didn’t know what it was.

‘Seemed impossible’

The interest rates Pettit said the bonds were paying also appeared high for municipal securities. He told clients they ranged from 8.85 percent up to 9.13 percent.

Hudson County has “not been floating bonds yielding 8.85 percent — at least not in the last two decades — as any look at the market for local government bonds would make pretty clear,” Kennelly said.

In a letter to another client, Pettit said Hudson County NJ MPT Authority was paying 9.01 percent.

It couldn’t be determined if the investments Pettit recommended were ever sold on the secondary market. He never made any mention of the secondary bond market in the letters filed as court exhibits. If such investments existed, they probably would have been considered too risky for clients at or near retirement based on the interest rates Pettit quoted.

Stephen Foster, the attorney representing the couple, said he was more suspicious of Pettit’s claim he had put almost $63,000 of his clients’ money into a money market account paying 5.43 percent. It would have been difficult to find a money market paying even half that rate in 2019 or 2020.

“Everything else seemed unlikely but that seemed impossible,” Foster said.

Pettit assured clients the money they invested with him was “insured up to $10,000,000 through our errors and omissions coverage.”

Henwood took that to mean that his principal would be guaranteed if his investments tanked.

In actuality, E&O insurance covers negligence and mistakes. It doesn’t cover losses if investments decline in value. Nor does it cover losses from criminal acts.

Pettit held his securities license with Triad Advisors until Sept.8. There’s no explanation on the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Investment Adviser Public Disclosure website for why the relationship ended.

An investment advisory firm has a duty to actively supervise its advisers. Failure to do so can lead to potential liability for a firm, said Matthew King, a San Antonio estate law attorney and financial adviser.

Whether Triad was maintaining oversight of Pettit couldn’t be determined. Triad representatives in Austin and Georgia didn’t respond to messages seeking comment.

But the firm has had supervisory problems. In December, Triad was fined $195,000 and ordered to pay more than $500,000 in restitution after the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority found it “failed to reasonably supervise representatives recommendations of an alternative mutual fund.” Triad neither admitted nor denied the findings but consented to the sanctions.

It’s “a lot of control and power to take on” when an attorney also becomes a client’s investment adviser, King said.

“It’s really important that you maintain each practice separately with a wall between them because the risk is, if you don’t do that, then in between these different hats you’re wearing, it’s possible to create a lot of confusion and potentially give room to defraud someone,” he said.

Dallas’ Robert Lewins, who practices law and serves as an investment advisory representative, explained how he keeps the two separate.

“I have two completely different email addresses,” he said. “I have two completely different sets of stationery, business cards. They are completely different.”

Pettit shouldn’t have been recommending investments on his law firm’s stationery, Lewins said.

‘Out in the cold’

The devastation allegedly wrought is only beginning to surface.

“Some of the stories of betrayal that I’ve heard are really — they’re difficult to hear,” San Antonio attorney Raymond Battaglia told Chief U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Craig Gargotta at a June 8 hearing.

In the case of one family, Battaglia said, Pettit promised a man on his deathbed that his wife would be taken care of. When the wife was on her deathbed, Pettit assured her that her daughter would be taken care of.

“Yeah, he sure did” take care of them, Battaglia said, his voice full of sarcasm.“I would say he did absolutely the opposite.” He’s been told $2.8 million of the family’s money is missing.

In an interview, he recounted receiving a phone call from a woman in her 80s who wanted to hire him to represent her in Pettit’s bankruptcy.

“She is living in an independent living facility … and was getting a check monthly from Chris,” Battaglia said. “And, basically, outside of Social Security, it’s all she had left. It’s kind of hard talking to someone like that and saying, ‘Your money’s gone. You’re not going to get any more checks.’”

Battaglia also mentioned during the hearing how Pettit’s bankruptcy schedules list him as holding or controlling the assets for a combination of 52 different individuals, partnerships, trusts and estates. Yet Pettit couldn’t describe the assets, where they are, or their value.

“I think (that’s) a clear red flag that all 52 of those accounts are diminished, if not stolen,” Battaglia said in court.

That came as a surprise to Angelita Vossler of Houston, who’s listed among the 52. She received a statement from Pettit for the quarter ended March 31 showing a balance of almost $360,000 in her account. She’s in the middle of having a house built in Brazoria County and was relying on that money to cover construction costs. She doesn’t know what she’s going to do now.

“I am 85, so I have no way to make up any of my losses,” she said. “I’m just out in the cold. I don’t understand how anyone could do what he did to people that trusted him.”

Henwood said he never got statements reflecting where his investments were held. Pettit would usually a letter, generally annually, listing the investments and their amounts and the interests they were generating, Henwood said.

According to Pettit’s personal bankruptcy filing, most of his assets are residential real estate — including a 7,300-square-foot Disney World mansion now listed for sale at $8.9 million. A house at 555 Argyle Ave. in Alamo Heights overlooking Olmos Dam is valued at $3.6 million.

His bankruptcy lawyer told the bankruptcy judge Pettit has “medically related issues” and may seek treatment in “in-care facilities.”

None of it makes sense to Henwood.

“He’s a prominent lawyer in town and he had a lot very wealthy investors,” he said. “Why would you give all of that up?”

More Stories

Win a Life of Adventure – The Ultimate Bucket List Adventure Giveaway

Derwent Chromaflow Cats Eye Tutorial

Old Cars Reader Wheels: 1942 Hudson 20-T